The Uniqueness Economy (Part 3): A Framework for Defending Human Agency

By Omid Sardari Senior ML Engineer, Founder of Memory Bridge, and AI Safety Researcher.

Note: This is Part 3 of the Uniqueness Economy series. After outlining the risks and influence patterns in Parts 1 and Part 2, we’ll now focus on concrete technical and political levers for defending human agency.

If you build, deploy, or invest in AI systems, you’re not a passive observer in this story. You’re helping define the defaults.

We need a framework that combines technical design, product choices, and policy pressure to protect human agency in the uniqueness economy.

I think about this in two layers:

- Section A: Technical levers – what engineers and product teams can build and adopt.

- Section B: Movement and legislative levers – what societies can demand and enforce.

Section A: Technical Levers

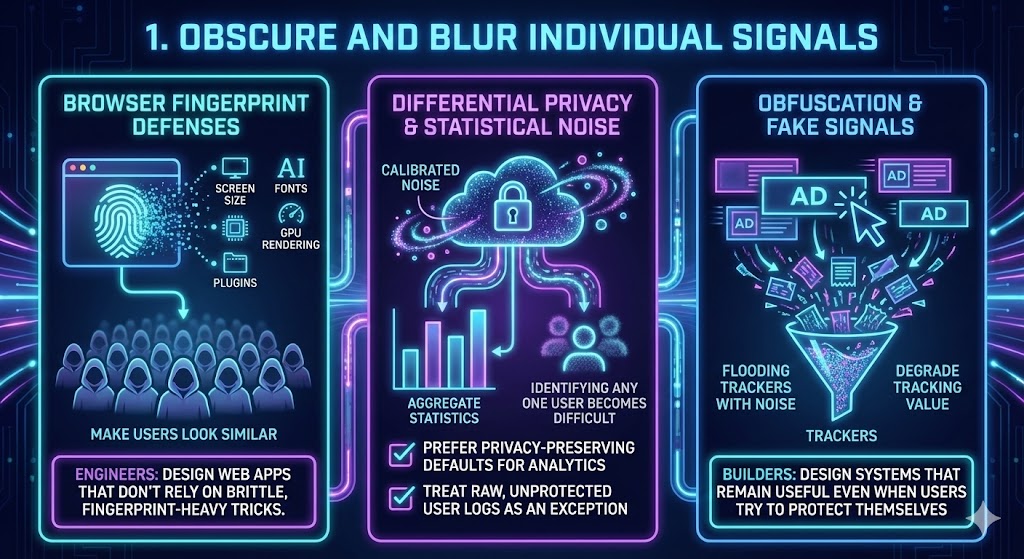

1. Obscure and Blur Individual Signals

Browser fingerprint defenses. Your browser exposes a surprisingly unique fingerprint: screen size, fonts, GPU rendering quirks, installed plugins, and more. Work in Firefox, Safari, and privacy tools tries to make users look more similar—like everyone wearing the same uniform—so that singling out individuals becomes harder.

The trade-off: the stronger the defenses, the more fragile some sites become. Engineers can help here by designing web apps that don’t rely on brittle, fingerprint-heavy tricks.

Differential privacy and statistical noise. Apple, Google, and others already deploy differential privacy in some telemetry pipelines. The idea: add carefully calibrated noise so aggregate statistics remain useful, but identifying any one user becomes mathematically difficult. This is not magic, and it has limits. More privacy usually means less granular analytics. But as engineers, we can:

- Prefer privacy-preserving defaults for analytics.

- Treat raw, unprotected user logs as an exception, not a baseline.

Obfuscation and fake signals. Tools like AdNauseam take a different approach: they deliberately click every ad they block, flooding trackers with noise. Individually, this is symbolic. At scale, it could degrade tracking value.

As builders, we can think about how to design systems that remain useful even when users try to protect themselves, instead of assuming perfect, honest telemetry.

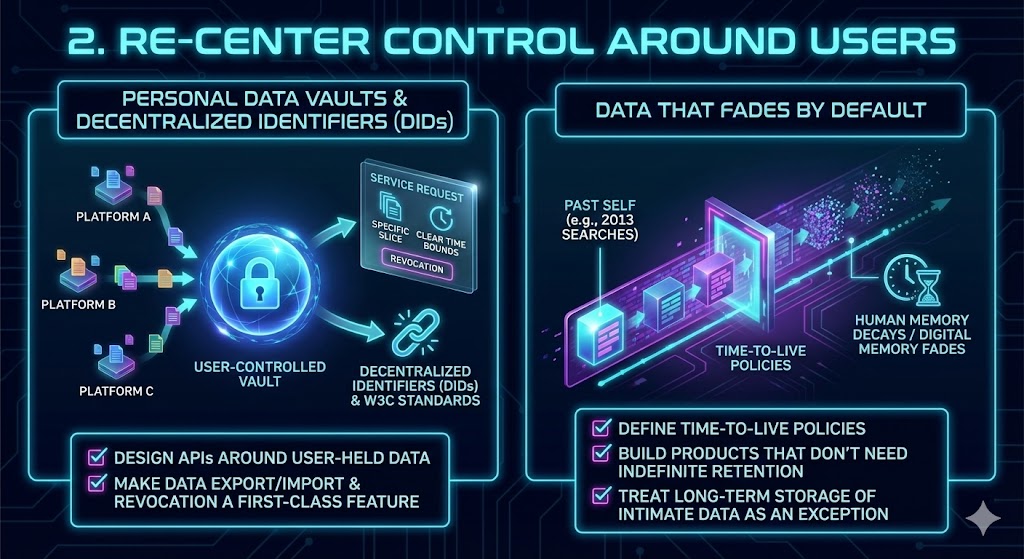

2. Re-center Control Around Users

Personal data vaults and decentralized identifiers. Imagine your data living in a user-controlled vault—not scattered across hundreds of platforms. Services would request access to specific slices of your information for specific purposes, with clear time bounds and revocation.This is one of the core motivations behind Memory Bridge.

Standards like Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and related W3C work already exist. The limiting factor isn’t cryptography—it’s adoption and product integration. If you’re a founder or engineer, you can:

- Design APIs around user-held data instead of platform-held data.

- Make data export/import and revocation a first-class feature, not a compliance afterthought.

Data that fades by default. Human memory decays. Digital memory doesn’t. That asymmetry traps people in their past selves. Some systems already implement partial decay (e.g., auto-deleting location history or limiting log retention). But we can go further:

- Define time-to-live policies for different data types.

- Build products that don’t need indefinite retention to function.

- Treat long-term storage of intimate data as an exception requiring justification.

If credit bureaus can expire negative marks after seven years, we can design AI systems that don’t keep your 2013 late-night searches forever.

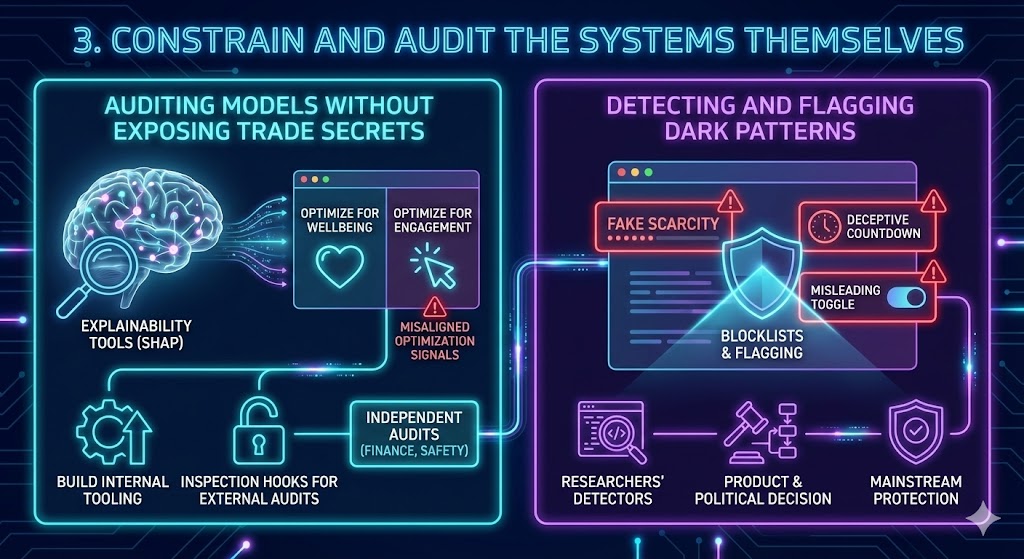

3. Constrain and Audit the Systems Themselves

Auditing models without exposing trade secrets. Techniques like SHAP and other explainability tools let us probe which features drive model decisions. Combined with robust evaluation datasets, they can reveal when systems optimize for engagement at the expense of wellbeing, or when proxies for sensitive attributes sneak in.

The challenge is not purely technical. Companies worry about exposing IP and legal liability. But we already have models for independent audits in finance and safety-critical industries.

Engineers can:

- Build internal tooling that surfaces misaligned optimization signals

- Support external audits by designing models and data flows with inspection hooks in mind.

Detecting and flagging dark patterns. Browser vendors already maintain blocklists for malware and phishing. Similar infrastructure could flag manipulative UX patterns: fake scarcity, deceptive countdowns, misleading toggles.

Researchers have already built detectors for many of these “dark patterns.” Turning them into mainstream protection is more of a product and political decision than a research challenge.

Section B: Movement and Legislative Levers

Technical work alone won’t fix incentives in a surveillance-driven economy. We also need social pressure and regulation that rewards privacy-preserving designs and punishes extractive ones.

The Corporate Response Cycle

If we borrow a page from the environmental movement, we can see a familiar pattern in how corporations respond to pressure:

- Denial – “Users don’t really care about privacy.”

- Privacy-washing – “We value your privacy” banners, with minimal changes.

- Differentiation – One major player uses real privacy as a market edge.

- Cascade – Others follow to avoid losing users and talent.

- New normal – Stronger privacy becomes table stakes.

As engineers, researchers, and founders, we accelerate this cycle when we

- Build and showcase viable privacy-preserving products.

- Publish open standards and reference implementations.

- Make it embarrassing to claim something is “impossible” that open-source projects already do.

Why Politicians Will Act (Even If They Don’t Care)

We don’t need to assume lawmakers suddenly become privacy philosophers. They will act when they perceive:

- That tech companies have disproportionate influence over elections.

- That scandals (breaches, manipulative practices) anger their constituents.

- That new rules create economic opportunities for local ecosystems (privacy tech, compliance tools, etc.).

Regimes like GDPR in Europe and CCPA in California show the pattern

- A few high-profile abuses + public anger.

- Legal frameworks borrowed, adapted, and hardened.

- Global companies forced to comply everywhere because regional exceptions are too expensive.

When engineers and researchers publish concrete technical standards—for data decay, differential privacy, auditability, and dark-pattern detection—those standards become ready-made regulatory hooks. Lawmakers can point to them and say: “This is the minimum.”

Conclusion: The Choice in Front of Builders

We stand at a fork.

Down one path lies a world where:

- Our minds become transparent to systems we don’t control

- Our uniqueness is harvested and diluted into synthetic clones.

- Our choices are guided by architectures we never agreed to, optimized for someone else’s objective.

Down the other path lies a future where

- Human uniqueness is treated as something to protect, not just model.

- AI systems serve as tools that amplify agency rather than quietly erode it.

- The economic gains of AI are shared more broadly, instead of concentrating around owners of behavioral data

The technology itself is not fated to be liberating or oppressive. But without deliberate intervention—by engineers, researchers, founders, policymakers, and users—we will drift toward a kind of digital feudalism, where a handful of AI platforms own the patterns that make us who we are.

I chose to become a privacy advocate because I believe in the second path. If you build models, design products, or invest in AI, you’re already helping decide which path we take. The question is: What kind of future will your code, your products, and your capital help create?