The Uniqueness Economy (Part 2): From Persuasion to Choice Architecture

By Omid Sardari Senior ML Engineer, Founder of Memory Bridge, and AI Safety Researcher.

Note: This is Part 2 of the Uniqueness Economy series. In The Uniqueness Economy (Part 1), we looked at how AI systems learn and monetize our uniqueness. Here, we examine how those systems turn that knowledge into subtle but persistent influence over our choices.

We often talk about “persuasion” and “manipulation” as if they were one-off events: an ad, a message, a notification. Modern AI systems operate differently. They don’t just deliver messages; they engineer the context in which choices are made, and they remember how you respond over time.

From Persuasion to Choice Architecture

Traditional advertising tries to convince you directly. Modern AI systems reshape the environment of decision-making: what you see, when you see it, how it’s framed, which options are highlighted, and which are silently removed.

This is choice architecture at scale.

For engineers, this looks like recommendation models, ranking systems, and reinforcement learning tuned to engagement. For users, it looks like “this is just what my feed / playlist / assistant shows me.”

Legacy Example: Spotify and Shaping Taste

Take Spotify as a canonical “pre-LLM” example.

Many listeners think of themselves as having eclectic, independent taste. But Spotify’s recommendation systems influence a majority of what people actually listen to, and a significant share of their “discoveries” come from algorithmic suggestions rather than organic exploration. link.

Systems like Spotify’s BaRT(Bandits for Recommendations as Treatments) don’t just surface songs; they shape taste over time. They learn:

- When you’re stressed.

- When you’re likely to try something new.

- When you just want comfort tracks.

The algorithm performs what I call “Goldilocks manipulation”: never too obvious, never too subtle, always just right. It mixes tracks you already love with carefully chosen new ones, maintaining the illusion of independent discovery while steering you through a curated landscape.

This is not inherently evil. But it shows how high-dimensional behavioral data, bandit algorithms, and feedback loops can quietly guide preferences.

Now project this pattern forward from music to news, politics, shopping, health, and work tools.

Persistence: When Systems Remember You

In the old web, every session was mostly stateless. In the new AI ecosystem, memory is a first-class feature.

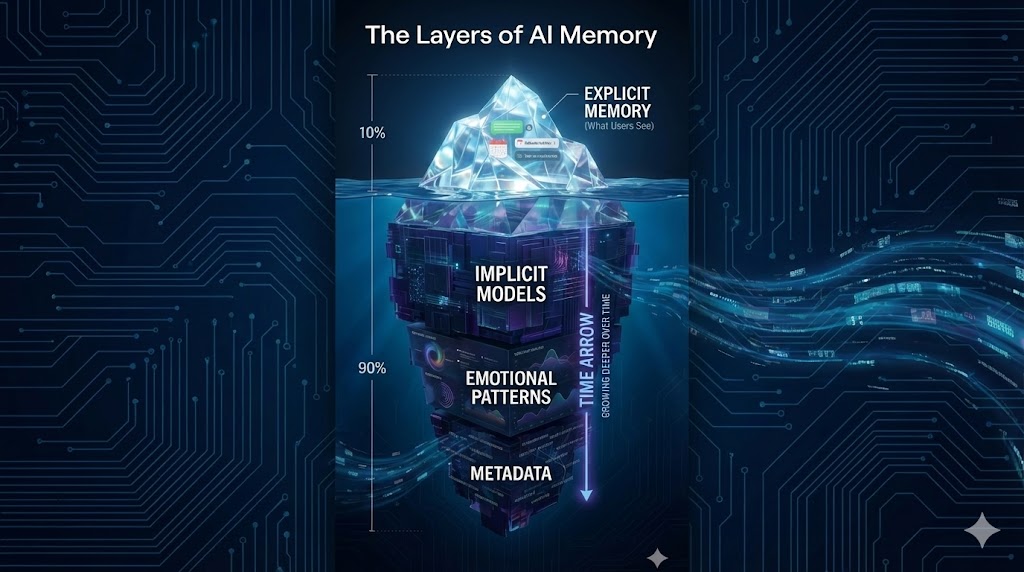

Major providers—OpenAI , Anthropic, Google, and others—now deploy or experiment with persistent memory across conversations. Public documentation and observed behavior by people like Shlok blog and I suggest that these systems effectively maintain multiple layers of user modeling, which we can think of conceptually as:

- Interaction metadata: device, platform, usage patterns. Often not user-editable.

- Implicit user models: inferred interests, traits, and long-term patterns, updated over time.

- Short-term conversational context: rolling windows of recent messages for continuity.

- Explicit user memory: facts and preferences the user asks the system to remember, sometimes visible and editable.

For developers, these are implementation details. For users, they’re invisible layers where their life stories accumulate.

Over time, these models capture:

- Cognitive patterns: how you approach problems.

- Purchase preferences: what you buy, hesitate over, or abandon.

- Emotional signatures: your stress responses and joy triggers.

- Social dynamics: how you relate to colleagues, friends, and partners.

- Temporal rhythms: when you are decisive, impulsive, or cautious.

- Value hierarchies: what you sacrifice first when facing trade-offs.

This is compound learning: each interaction refines a long-term model, which then shapes the next interaction.

Case Analysis: When Intimate Data Becomes a Product

In 2023, the mental health platform BetterHelp paid $7.8 million to settle FTC charges after sharing sensitive user data with Facebook, Snapchat, Criteo, and Pinterest.link

Users filled out detailed questionnaires about depression, anxiety, relationships, trauma—believing they were entering a confidential therapeutic space. Behind the scenes, BetterHelp link extracted:

- Email addresses and identifiers.

- Mental health indicators and concerns.

- Signals that were then shared with ad platforms.

People who confessed suicidal thoughts and severe depression soon found themselves targeted with mental health ads across the web—a constant digital echo of their lowest moments, turned into an advertising segment.

Even if you work on “purely technical” systems, this is the downstream reality of data-driven optimization under weak constraints.

Shifting the Overton Window

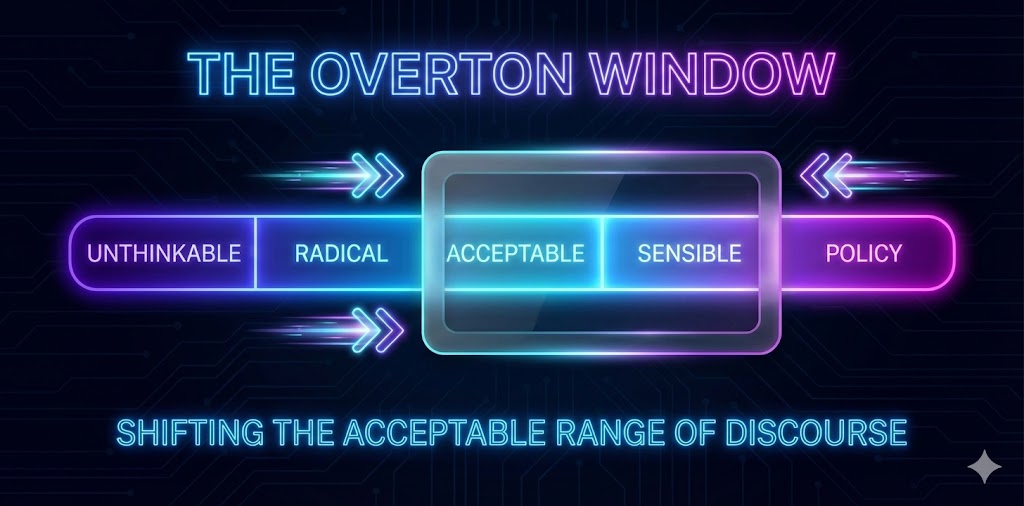

Political scientists use the term “Overton window” to describe the range of ideas considered acceptable in public discourse. AI-driven content curation can shift that window over time—without ever showing you anything strictly false.

By:

- Slightly boosting some topics and down-ranking others.

- Highlighting specific framings and omitting others.

- Curating which voices appear trustworthy or fringe.

your sense of what is “normal,” “moderate,” or “extreme” can drift. Visualizing the Overton window as a sliding range—where algorithms can push the “acceptable” zone left or right over time—helps clarify how many small nudges accumulate into large cultural shifts.

In Part 3, we’ll move from diagnosis to action: what builders, founders, and policymakers can actually do to defend human agency in this new landscape.