The Uniqueness Economy (Part 1): How AI Models Your Identity & Architectures Your Choices

By Omid Sardari Senior ML Engineer, Founder of Memory Bridge, and AI Safety Researcher.

Note: This is Part 1 of a three-part series on the Uniqueness Economy.

Introduction: The View from the Inside

I have spent the last several years working with machine learning systems—as a researcher, a founder building Memory Bridge, and an AI safety advocate. Most of my work is practical: building and debugging models, shipping products, and trying to make tools that are genuinely useful.

From that vantage point, I keep seeing the same pattern: as these systems improve, they do not just learn about “users” in the abstract. They learn about us as individuals—our habits, our routines, and our blind spots.

I do not claim to have all the answers. I am part of the ecosystem creating these systems. But I am writing this to name the risks I see from the inside: not to condemn the technology, but to be honest about how easily it can cross the line from serving people to architecting their choices.

This is written for people like me—ML engineers, builders, and founders. We need to take these questions seriously now, while we still have the power to shape the defaults.

The Coming Uniqueness Economy

The Voting Analogy: From Information to Influence

Imagine a political campaign that doesn’t just know your voting record, but also knows:

- You’re more receptive to messages about economic security right after paying your mortgage.

- You trust information more when it comes from a specific local news anchor.

- You’re more easily swayed by arguments framed in a particular emotional tone.

On the surface, that sounds like “relevant information delivery.” But now imagine thousands of micro-targeted campaigns using these insights not to inform you, but to nudge your opinions on hundreds of issues, quietly architecting your consent without a single public debate.

Cambridge Analytica Was Just the Preview

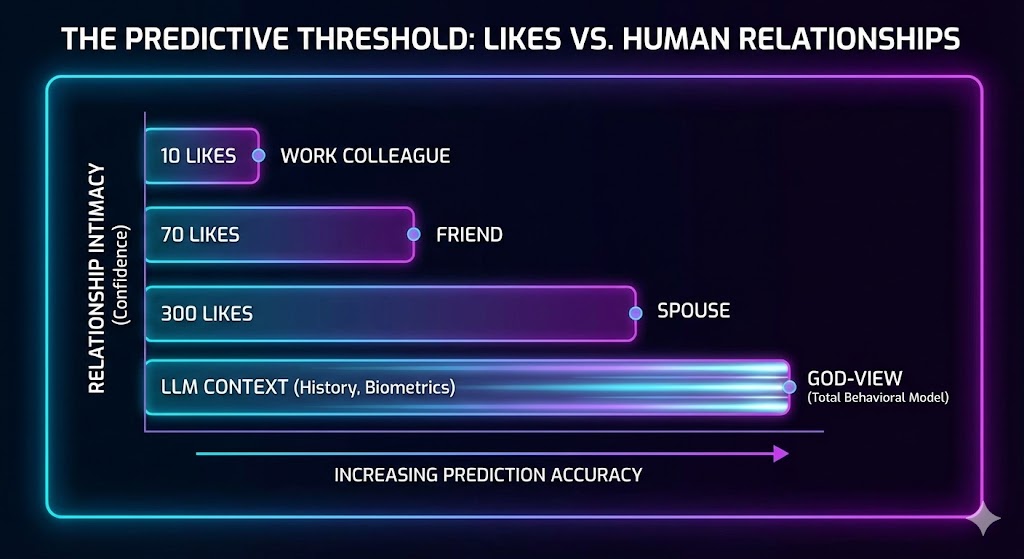

In 2013, researchers at Cambridge University link showed how much can be inferred from seemingly trivial data: they could predict intimate traits from nothing more than Facebook “likes,” not posts or photos, just the icons we tap without thinking.

The results were startling:

- 10 likes: they could judge your personality better than a work colleague.

- 70 likes: more accurate than your friends.

- 300 likes: they knew you better than your spouse.

The model reached around 95 % accuracy for race, 93 % for gender, 88 % for sexual orientation, and 85 % for political affiliation—starting from innocuous digital traces. llink

Cambridge Analytica saw an opportunity. When the original researchers refused to weaponize these models for political campaigns, others stepped in. What began as academic work on personality prediction became a playbook for large-scale influence.

That was classical machine learning, built on a thin layer of behavioral data. Today’s language models and AI ecosystems have access to orders of magnitude richer information

- Complete conversational histories.

- Real-time emotional indicators in writing patterns.

- Problem-solving approaches across many domains.

- Temporal patterns in decisions.

- Linguistic and conceptual evolution over years.

We are rapidly moving from “we can infer your traits from sparse signals” to “we can model your behavior from deeply contextual, longitudinal data.”

The Uniqueness Valuation Problem

Research link from MIT’s Digital Economy Lab suggests that as automation advances, human economic value increasingly comes from unique perspectives, creativity, and judgment—the parts that are hardest to automate.

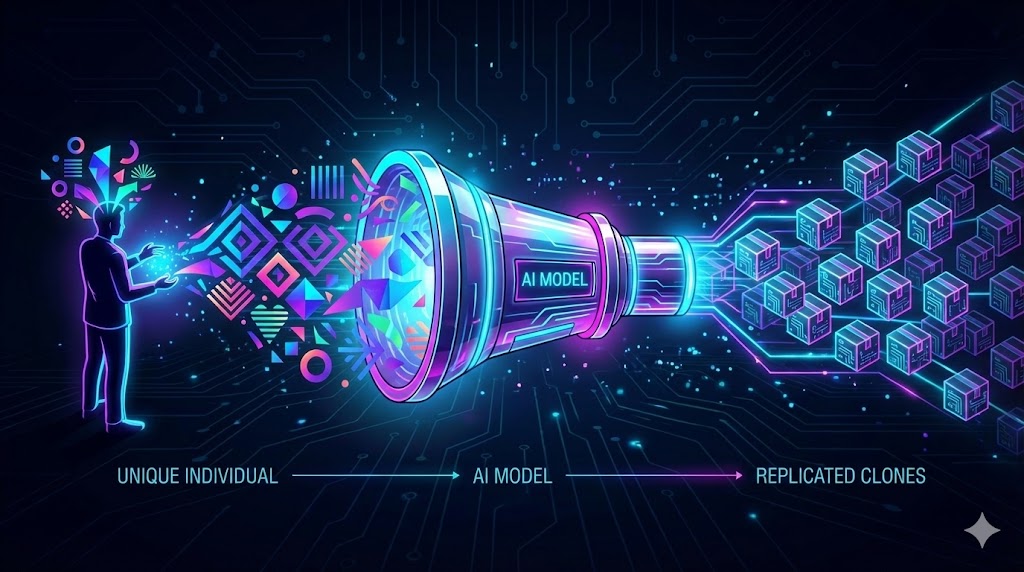

But what happens when those unique traits are modeled, replicated, and scaled by AI?

Consider a freelance graphic designer whose style becomes part of a training dataset. Once an AI can generate unlimited images “in the style of” that designer at near-zero marginal cost, their economic moat—their uniqueness—shrinks dramatically. The system doesn’t need to hire them; it just needs enough of their work to synthesize something close.

I call this uniqueness dilution: the extraction and replication of what makes you economically distinctive.

Documented Example: Voice Synthesis Markets

The voice acting industry offers an early warning.

Companies like Replica Studios and others train AI voice models on real actors. Some performers have sold rights to their voice data for a one-time payment, only to watch their synthetic “clone” narrate content, ads, and games at scale—generating value they no longer participate in.

Their voice—arguably one of the most personal forms of uniqueness—becomes a reusable asset in someone else’s infrastructure.

This is not just about “privacy.” It’s about who captures the upside from human distinctiveness.

In Part 2, we’ll move from what is being learned about us to how those insights shape our environment and choices—often without us noticing.